How “Reframing” Results In Happy Parents (And Kids)

Written by Katie Hintz-Zambrano

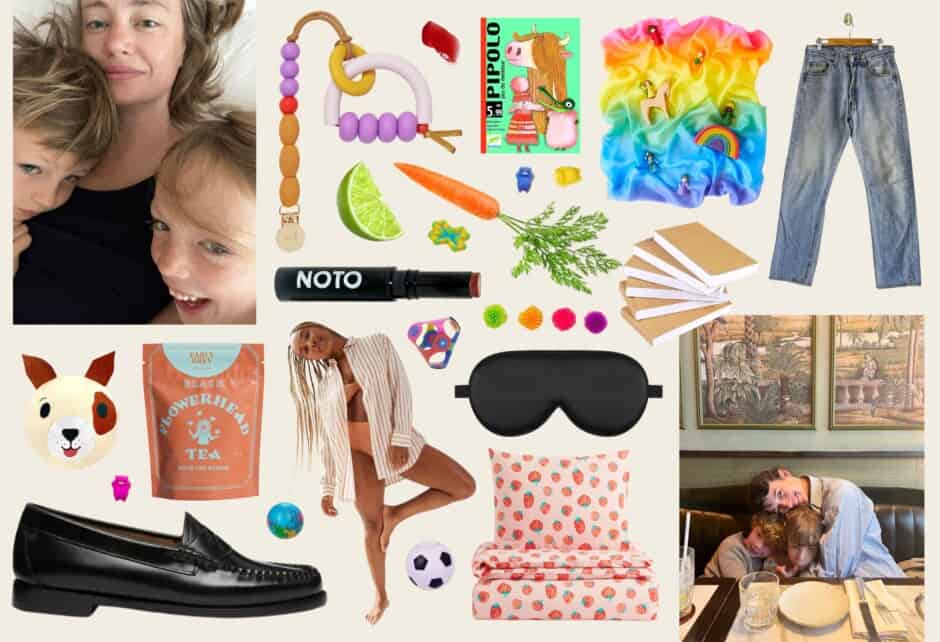

Photography by Ulla Johnson photographed by Maria Del Rio

For those of you who have missed our series on Danish Parenting, it’s baaaack. With The Danish Way of Parenting authors Jessica Alexander and Iben Sandahl leading the way, we’ve already discussed the concepts of the power of play, the importance of teaching empathy, no ultimatums parenting, cozy time (a.k.a. “hygge”), and the general rules regarding these international parenting techniques (which supposedly lead to the happiest kids/people in the world). Now the authors (who just signed on with Penguin to release a new-and-improved book in August 2016) share the idea around Danes constant “reframing” of events, perhaps one of the harder concepts for some stressed-out parents to grasp. Food for thought, below!

What exactly is “reframing”?

“The Danish way of reframing is a way of looking at life in a softer, more positive, or less limiting way. It is something the Danes do naturally and they pass this skill onto their children. We believe it is one of the reasons that Danes grow up to be consistently voted as the happiest people in the world. If you ask a Dane about the weather when it is freezing, gray, and raining outside, they will unwittingly answer: ‘There is no bad weather, only bad clothing’ or ‘I am glad we can get cozy inside at home tonight.’ If you say, ‘Too bad it’s the last day of our vacation,’ they might reply, ‘Yes, but it is the first day of the rest of our lives.’ If you try to get them to focus on something really negative about any topic, you may be mystified at the way they can reinterpret it. Danes are what psychologists call ‘realistic optimists.’ They don’t negate negative information like overly optimistic people with rose-colored glasses. They tend to be brutally realistic about life, but they are also incredibly gifted at finding angles of reality that aren’t so dark, upsetting, or negative. It is a bit like what happens in an art gallery.”

What do you mean?

“The metaphor we use about reframing in the book is to imagine that you are in an art gallery. You see a painting, which you think looks somber and dark. You decide it is a negative picture and you want to move on, but the guide stops you to point out that there are many other details in the painting you hadn’t noticed before. There is a child laughing in the distance, the light streaming through the window is extraordinary, and there is a birthday gift in the shadow on the table. The mood is actually happy and loving. It’s not somber or dark at all. Your whole experience of the painting has changed and the way you retell your experience of the painting will be totally different as well. Reframing is about looking at life, putting it into a bigger frame, and finding the less negative details. And the guide to finding these details is you.”

How does one use language to reframe?

“It’s important to remember that our language is a choice. It is a frame through which we perceive our world. Thus, when we say things like ‘I have no willpower, I am so fat,’ ‘I hate my mother-in-law,’ or ‘I am terrible at cooking,’ these statements are very defining and limiting. ‘I am trying to eat healthier and exercise more,’ ‘My mother-in-law is a great grandmother to the kids,’ or ‘I enjoy trying new recipes that are simple,’ are completely different ways of looking at exactly the same things. These sentences are less limiting and feel completely different. By reframing what we say into something more supportive and less defining, we can actually change the way we feel about our life and others. Reframing has actually been proven to change our brain chemistry. It can improve the way we interpret fear, pain, anxiety, etc.”

How can one use reframing with children?

“Reframing with children is about the adult helping the child shift focus from what they think they can’t do to what they can. When a child uses limiting language like ‘I hate this, I can’t do it’ or ‘I am not good at that,’ they are creating a negative storyline for themself. But we as parents can help them focus on other details in their stories that are less negative without telling them how to feel. This can be true about what they say about themselves, about life, and about others. If they hate school, we can focus on things we know they do like in school and lead them to talk about those aspects. Not by putting words in their mouth, but by gently leading them there. Maybe there is a teacher they love or an art class they enjoy. By focusing on those aspects it helps change the way they see school. If they have a hard time with a friend, we could ask questions about another time they had fun with that friend. We as parents can help children focus on better, more supportive storylines without saying ‘You shouldn’t be/feel like that’ or label people negatively. Labels, ultimately, can be dangerous.”

How so?

“It is a very common practice in our society to label. ‘He is mean,’ ‘She is selfish,’ ‘He has ADHD.’ Labels are dangerous because they can become self-fulfilling prophecies. Think about how much of what you believe about yourself came from what you were told as a child. Were you lazy, sensitive, not a math person, or shy? So much of what we believe about ourselves comes from our childhood. It is hard to shake these labels, but we absolutely can with reframing. Even as adults, we can learn to build up new stories about ourselves and shake those old labels.”

Children are at risk of becoming these labels?

“Yes. When a child continually hears things like ‘She isn’t good at sports,’ ‘He isn’t very academic,’ or ‘She is too sensitive,’ they try to make sense of what they hear and identify with it. So, the more they hear people say these things (and they do much more often than adults realize they do), they begin to build coping strategies based on a mistrust of their own abilities in the face of new challenges outside of these beliefs. A boy who ‘isn’t very academic’ may not want to study because it doesn’t fit his label. Someone who hears ‘she hates sports’ may not participate in new games she might actually like. It is so important for us as parents to try to find the other side of negative labels and talk about those instead. ‘A stubborn child,’ for example, may be very persistent or exhibit great leadership qualities. ‘The distracted child’ may be very artistic and loves to create things. ‘The antisocial child’ may be deeply intellectual and empathic. By looking for and talking about the more positive details, we help children learn to reframe naturally. And this will change their whole experience of life. The language we use matters. Reframing takes practice, but it really does work in improving happiness.”

For more information on reframing, please check out The Danish Way of Parenting: What the Happiest People in the World Know About Raising Confident, Capable Kids. You can also visit Alexander’s website and Facebook page.

Share this story