Mom Talk: My Refugee Mother Returns Home

Written by Mona Hajjar Halaby

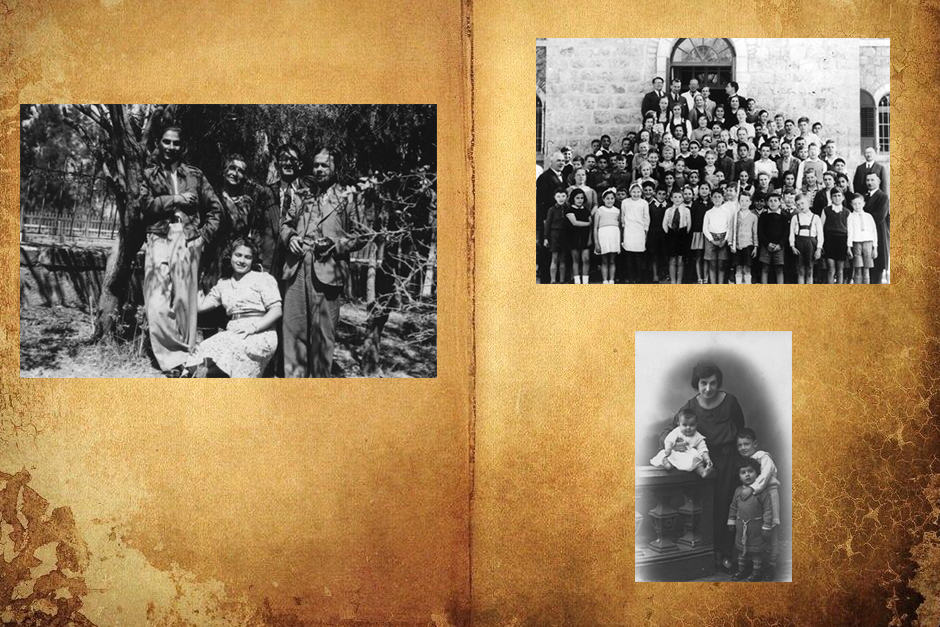

Photography by Photos courtesy of Mona Hajjar Halaby

Today’s Mom Talk essay is an excerpt from Mona Hajjar Halaby’s upcoming book, In My Mother’s Footsteps: A Palestinian Refugee Returns Home (August 2021). In it, the Palestinian-American educator, writer, and social historian interweaves the story of her mother’s life as a refugee and her own sabbatical year teaching conflict resolution back in her family’s homeland. Below, a tale of longing both from Mona’s perspective and her mother’s (via a letter she sent Mona).

As a small child when I walked about with my mother, I always clutched her hand and let her guide me. It was smooth and easy, like gliding on ice. Looking up at her from my tiny stature was like beholding a superhero by my side; Mama was larger than life. Her handgrip was firm and decisive, like she meant business, like she knew where she was going, yet it was also warm and tender, like “I love you, and I’ll take care of you.” The puffiness of her palm reminded me of a loaf of warm pita bread, and when she laced her fingers into mine like a pretzel, I felt safe. I would have walked with her to the ends of the earth.

Nothing could pry us apart, except that life happened, and when I grew up we found ourselves worlds apart. In my twenties, I moved away from home in Geneva, Switzerland, and settled in California, USA to be with the man I loved and to pursue my graduate studies. Mama, on the other hand, a Palestinian refugee in exile from her homeland, remained in Geneva with my father and sister. Even though I wasn’t born in Palestine, my mother fed me stories about her childhood and youth, and I grew up knowing that Palestine ran in my blood. I was enamored by the joyful and exotic life my mother led in Jerusalem, by the happy days that came crumbling down when she lost her home during the Arab-Israeli War of 1948.

I also visited Palestine repeatedly, but never lived in my homeland, until 2007 when the Ramallah Friends School (RFS) in the Israeli Occupied Territories invited me—a teacher by profession—to train their faculty for one year in the facilitation of class meetings and non-violent communication, my specialties. I was hired to teach the students how to problem-solve and resolve their conflicts in a direct and peaceful manner. That year, I grew as a teacher while witnessing firsthand the effects of the Israeli Occupation on school-age children.

Living in Ramallah, I had come to know every corner of Palestine like the palm of my own hand. By the time my mother joined me for that epic visit, I was a woman in my fifties, and Mama had grown old with signs of an arthritic body and a fuzzy memory. She held my hand, or walked arm in arm with me, as I helped her negotiate the narrow cobblestone alleys of the Old City and the streets of Lower Baq’a in West Jerusalem. Years ago, I had dreamed of being guided by Mama down the souqs of the Old City and the leafy streets of her neighborhood. I wanted to glide on ice with her again and feel her decisive and confident stride. But alas, it was not to be. Now with our roles reversed, I had become her legs and her memory.

My story can be told in two voices, my mother’s and my own, the past and the present intertwined. She wrote me letters during my year in Ramallah, letters that told her story, her love of Jerusalem, and her loss of Jerusalem. I also kept a journal. Daily I wrote about my work at the school and the challenges teachers and students faced while living in a militarized, occupied town. I wrote about my impressions of living in my homeland, a place I had inhaled since I was an infant, a place I had dreamed about and imagined for so many years. I started the journey not knowing what lay ahead, and how it would change me, but eager to make a difference in my homeland and connect with my roots. Every building, every alley, every church anchored me to Jerusalem, to my genealogy, as though my past was imprinted on the stones.

I wasn’t born there; I never lived there, but I was from there.

********

My Sweet Daughter, Mona,

It’s freezing today. Even with the heater on full blast, I feel cold to my bones. I am reminded of the winter of 1948—deadly cold. I kept our living room warm with a small coal-burning stove. Practically every night we heard bombings and shootings in our area. Our friends, the Habesch, who lived in Talbiyyeh, were luckier than most. They contacted the British Police when one morning they found a string hanging from their mulberry tree with an awkward-looking package hidden among the leaves. They followed the string and saw that it was buried in the ground in a sort of trench. They suspected a bomb. The police came, evacuated the entire neighborhood, diffused and dismantled the bomb. Had it exploded, it would have destroyed the entire block including the British Mandate court and the Italian Franciscan Nuns’ School. Not long after, in Qatamon, the Muna family and Issaevitch family houses were bombed.

Fortunately, the families were safe.

Nighttime was the most dangerous time, as the Haganah and Irgun were planting bombs in the residential neighborhoods of West Jerusalem, with the justification that Palestinian guerrilla fighters were holding their meetings in those homes. Baloney! The real reason was to create fear in us and drive us out of our homes. And that’s exactly what happened.

Well, you might be thinking, “So, how did you protect yourselves, Mama?” I’ll tell you how. My brother Daoud with other young men in the neighborhood formed their own protection force and took shifts at night to patrol our neighborhood. The living-room floor was covered with mattresses for the men who took turns sleeping between their shifts. These were sleepless, perilous nights, my Darling. I took short naps curled up on the couch and woke up during the “changing of the guards.” I made coffee for the men while they listened to the latest news on the wireless.

During that time, we didn’t have a full picture of what was happening. We didn’t understand that we were systematically being driven out of our neighborhoods in order for the Zionists to incorporate West Jerusalem, which had been part of Palestine per the UN Partition Plan into Israel. Every day more houses in the neighborhood were attacked and bombed—the houses of the Shahines, Anabtawis, Campbell-Browns, Budeiris, and Freijs, to name a few. Every day brought another casualty and more fear for the remaining of us. Were we going to be next?

My brother Afif was extremely shaken by these events. He was terrified. Every time he heard a loud sound in the neighborhood, he would scream, “Hajamu al-Yahud!” (“The Jews are attacking!”) Daoud switched bedrooms with him, hoping that the back bedroom would be quieter, but Afif was not reassured.

Many neighbors and friends left their homes for safer grounds, quickly grabbing a suitcase and arranging for a taxi to drive them to Beirut, Cairo, or Amman. They needed to protect their loved ones. When our beloved upstairs neighbors, the Nuwayhids, came by one day to say goodbye, I broke down and cried, “But Imm Khaldoun, I’ll be the only one left. I’ll be all alone.” Imm Khaldoun had taken good care of me since Mama’s death and I had come to rely on her. She reassured me that she’d be back in a few weeks, but that was the last time I saw her. Like in all wars, we thought that once the fighting subsided we would be returning home. Little did we know that we would be losing our homes and our homeland forever.

Papa began to worry about us and decided it was best to send Afif and me to Tante Afifeh, our maternal aunt, who lived in Alexandria, Egypt, until the situation calmed down. I didn’t want to leave. I wanted to fight for my country, but Papa convinced me that I was helping by taking Afif away from the bombing. This was the worst thing that could have happened to me. I couldn’t fight; I didn’t have the right to fight for my country. If I had left my country after a battle, then perhaps I would have been able to accept it. You know, our house was like any other house in the world. It had a garden; it had chairs; it had a couch; it had tables, and food in the pantry. But all this didn’t matter. It was my family, my friends, Jerusalem that I had to leave behind and that’s hurting me to this day.

So, I packed my little suitcase with a few summer dresses. I anticipated coming back in a couple of weeks. Luckily, Afif, who was enamored with photography, packed his camera and the family photo albums. We hugged Papa and Daoud at the gate of our house. “See you soon, Allah ma’kum (Godspeed),” said Papa, and then Afif and I walked together to the bus stop on Bethlehem Road and boarded the bus to Cairo, not realizing that we would never be allowed to return home.

Sometimes at night when I can’t fall asleep, I say to myself, “Zakia, let’s return to Jerusalem. Let’s walk its streets.” I do this to see if I still remember all the streets. Sometimes I come to a dead-end street and I say, “Now, do I turn right, or should I go left?” And finally, I fall asleep.

Oh, my goodness, where did I take you today, my dear Mona? To hell and back, huh? I wonder if I’ll be able to fall asleep tonight, but if I can’t, then I’ll gladly walk the streets of Jerusalem again.

I love you dearly, my precious Mona.

Your Mama,

Zakia

Are you a mother with something to say? Send us an email to be considered for our “Mom Talk” column.

Share this story