Mom Talk: Learning to Mother Without One of My Own

Written by

Photography by

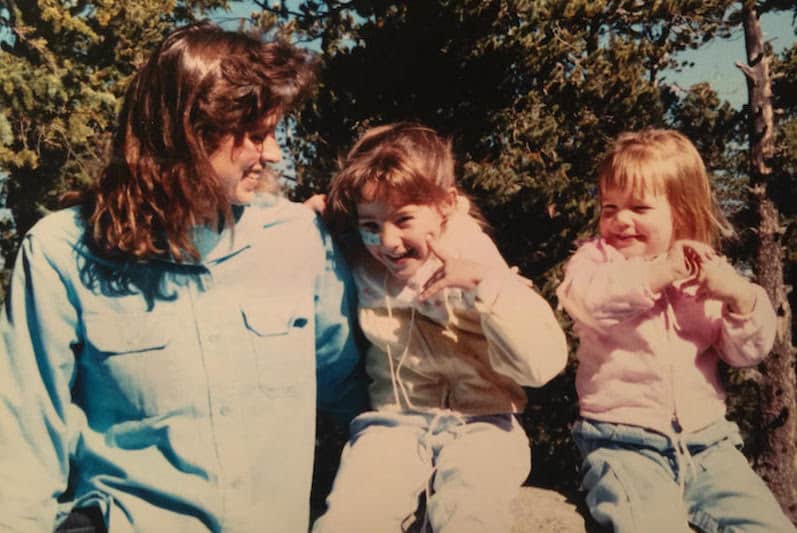

Photo courtesy of Claire Roeth

Whether your mom lives down the block and drops in to help with dinner and bath time on a regular basis, or she’s across the country and best known to her grandkids via Facetime, or she’s someone who only exists in photographs and faded memories, the many ways a mother is woven into our being is something nearly impossible to fully comprehend. Claire Roeth, who lost her mom as a teenager, writes honestly and beautifully about how having children of her own made her feel the loss of her own mother that much more acutely, and how raising her small kids alongside her sister was a salve to some of that sadness.

I’m driving southbound on I-25, just north of Denver. The mid-day, mid-summer sun is harsh and I squint, scanning the horizon, while my young daughters nap in their carseats. The girls and I usually live in the Midwest with my husband, their dad, but we are in my home state of Colorado for the summer. We’re staying with my aunt sometimes, my dad now and then, my sister mostly. Solo parenting is exhausting, and traveling all the time with two children under the age of three can be excruciating. I’m doing it because I have to find my mother.

I look for clues in the homes of my family. At my grandmother’s house I scour old family albums, analyzing every expression on my mom’s young face for hints about who she was, who she became, and, most mystifying of all, who she would have been now. I beg my dad to remember something, anything, about my mom as a young mother or their experience of parenthood in general, but memory is not his forte and neither are the trivial, if vital details of raising young children. Sometimes my sister can fill in holes or inaccuracies of my memory, but the limits of her experience of our mother are much the same as my own. Besides, my sister just had her first baby, and while it feels good to have a compatriot in the trenches of motherhood, she is, as I was, completely engulfed in the haze of keeping a newborn baby alive and well.

I am looking for my mom in Colorado, because I know she’s not in Ohio. I’m looking for my mom, but I know I won’t find her, not really, because she’s been dead for fifteen years.

When you give birth, if you can feel, what you feel is your body splitting open. You feel your insides flattening, your body stretching and ripping, every single bit of strength and effort concentrated on the biggest and most wonderful undertaking of your entire life. And then, through the flames of pain, a child: a head, a jumble of limbs breaking loose, a rush of fluid and a sudden, brilliant release of pressure. There’s nothing like nine months of pregnancy to drive home the point that your body is changing, and yet in one instant you become a mother and suddenly your body is the least of it. The world you knew before vanishes, the person you were before gone with it. Nothing can prepare you for the experience of coming face to face with your child, and I find even now that the first thing I wrote after my first daughter was born is still the truest thing I can say about it: there are no words for this magic.

Still, my bottom hurt (a lot), my nipples wouldn’t stop bleeding, and figuring out how to care for a newborn was completely consuming. And then it turned out that being a mother to a toddler was also consuming, and then being a mother of two was the most consuming thing of all. So it was, with all this consuming going on, that I failed to realize that when I split open to let the baby out on that unseasonably warm October evening, something else broke loose, too.

At first I could only identify the shift as a problem with physical place: Ohio was the problem. The dreary winters, proximity to my well-meaning but overbearing in-laws, even the predictable kindness of Midwestern strangers. Colorado was the antidote, the land of sunshine, mountains, and my own family legacy. I clung to this conviction as I packed our bags, and keep clinging until, a few weeks into our summer, I realized the thing that was missing in Ohio is missing in Colorado, too. And that’s when it hits me, driving eighty miles an hour down the highway that the problem isn’t geographic, after all (but spend the month of February in Ohio and you’ll see why I thought that was it). The problem is that in becoming a mother I had lost mine all over again.

Searching for my mom takes a heavy toll, and solo parenting makes me tired and irritable. I am perpetually folding and unfolding the stroller, feeding children and changing diapers, putting babies to sleep and retrieving them when they wake, each task I accomplish immediately creating the need for its opposite. We spend most of our time at my sister’s house: my sister, her husband, their newborn baby, my two girls, two dogs, and me all under one small roof. We step on each other’s toes and hurt each other’s feelings, because we are human and because we don’t have enough room or sense not to. But when I wake in the night to nurse my baby I can see the soft glow of the lamp in the living room, where my sister sleeps on the couch next to her newborn daughter’s bassinet. Sometimes we are sitting up nursing babies together, separated by a wall instead of a thousand miles. Sometimes I can hear her quietly singing “Over the Rainbow” to my niece, a song our mom sang to us. My sister and I take walks, our babies in strollers, dogs at our sides, chatting casually as though we are neighbors in real life and not just unconventional housemates for the summer.

In watching my sister parent I see myself in the early days of parenthood: the same singular focus, same propensity for anxiety, same quickness to chastise our partners. As weeks turn to months I start to notice something else. Her body is changed by the birth of her daughter, but it’s more than that. Something is slightly different about how she wears her hair, the clothes she chooses from her closet, the way a watch sits on her wrist. Her way of simply being feels more natural. Sometimes I look at my sister and see our mom, partly a physical resemblance, but mostly some other intangible quality I can’t quite put my finger on.

Summer comes to an end and the girls and I go back to Ohio. My dad drives us back, and when I drop him off at the Columbus airport, I cry. I sit in the silence of our own house, so much space to ourselves after staying in spare bedrooms, and the loneliness is oppressive. I am exhausted from the travel and parenting, but also from the endless searching. My time in Colorado feels like a failed pilgrimage: I have traversed thousands of miles, reached the outer limits of my physical and emotional endurance, and yet I have turned up nothing. My mom feels as lost to me now as she ever has.

One night several months later I nurse my almost-one-year-old to sleep, running my fingers across the bridge of her nose, the curls of downy soft hair behind her ears, her plump cheeks. There is nothing sweeter than the sound of a sleeping baby, the breaths light and somehow heavy at the same time, airy like a wind instrument, rhythmic. Part of me itches to put her down so I can start to tackle the always-daunting list of things I should do, but I stay a little bit longer because I realize there are not very many times in life when you can sit and hold a sleeping baby. Your own children are not children for long, in the grand scheme of things, and the next sleeping baby I hold may well be my own grandchild. If I am luckier than my mom.

When I do at last put the baby in her crib the toddler is ready for bed and asks if I will rock her, too. She is changing so fast, not a baby anymore but sometimes I can tell she misses the comfort of being one. To watch your children grow is to witness a thousand rebirths and deaths: who they were, who they are, who they will be. I settle into the chair with my sleepy child, her long hair spilling over one arm, long limbs over the other. She rests her head on my chest and something in me stirs. It’s not a specific memory but a deep sense of the way things were: years of moments all stacked together, a collective sense of the physical shape of my mom’s chest under my cheek and the lightness I felt when I had her to rest on.

I can’t find my mom in Ohio or Colorado or anywhere else, because the only place she is anymore is within me. I remember reading that halfway through pregnancy a female fetus has developed all the eggs in her ovaries she will ever have. My would-be daughters, two microscopic oocytes among millions, were created when I was in my mother’s womb, like the Russian nesting doll my mom saved from a family trip when she was in high school. I will never know the delicious comfort of calling my mom when I am drowning in the daily tasks of mothering small children. She will never come over to my house and say, “take a nap, I’ve got this.” I cannot ask her how she dealt with a two-year-old’s illogical tantrums or a one year who still won’t sleep through the night. But I can feel her hands in mine as I soothe a crying child, her laugh echoing in mine as I find the hilarity in the many disasters of living with unpredictable small children. And I can call my sister, a soul mate forged in the same womb I once occupied. She can share her own stories of mothering her daughter, a daughter who was once an egg in the same womb as my little eggs. My sister, her daughter, my daughters, me: we all have something in common. We come from the same magic.

Are you a mother with something to say? Send us an email to be considered for our “Mom Talk” column.

Write a Comment

Share this story

Thank you for this.

Beautiful and moving. thank you

I think this is the most beautiful mom talk piece I’ve ever read. Thank you so much for sharing Claire.

The experience of becoming a mother without my own was exactly the same. Thank you so much sharing this and putting it so eloquently.