The German Art Of Raising Self-Reliant Kids

Written by Katie Hintz-Zambrano

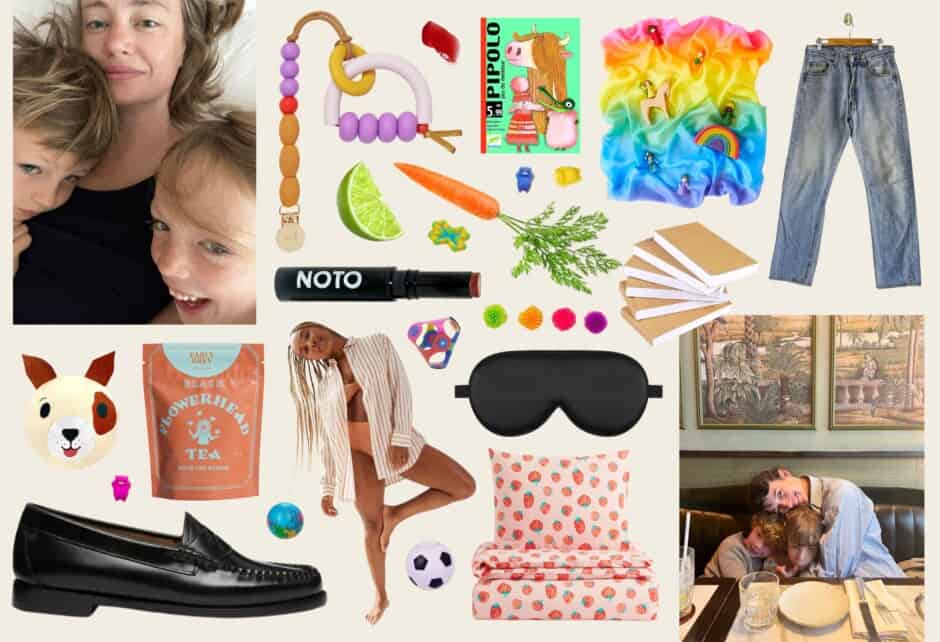

Photography by Shirley Erskine-Schreyer's daughter, photographed by Lina Gruen

As soon as we got wind of the book Achtung Baby: An American Mom on the German Art of Raising Self-Reliant Children back in September, we were counting down the days until we could get our hands on a review copy of what sounded a bit like the uber-popular and much-gifted Bringing Up Bebe, with a new international twist. Now that we’ve actually read Achtung Baby (which came out yesterday), we can attest that it is so, so much more. In fact, it’s now in our personal hands-down favorite parenting books list (and we’ve read a lot).

Written by journalist and mother-of-two Sara Zaske, who recently found herself living and raising young children in Berlin when her husband’s job stationed the family in the German capital for 6 1/2 years, the book is incredibly well researched and incredibly eye-opening. For example, did you know that by second grade German children routinely walk to school alone? Or that homeschooling in Germany is against the law? Or that some playgrounds there encourage children to play with fire (not while being watched like a hawk by a parent)? Experiencing this hands-off German parenting style firsthand, Zaske tells us “it radically changed how I saw myself as a parent and how I parent today.” We think after reading our interview with her below—and the book cover-to-cover—some of you might just feel the same way.

How would you explain the main tenets of German parenting?

“They highly value self-reliance. For German parents that value is so high it conquers the fears. They, of course, have the same fears that American parents do. They talk about horrible abductions that have happened or traffic accidents or what if your kid gets hurt or lost. They’re worried about those things, too. The difference is they don’t let those fears paralyze them or dictate what they do with their kids. To mitigate that type of fear, what they try to do is prepare their kids for risk and challenges. They teach them how to walk to school and deal with the traffic. There’s a lot of preparation before the kids are allowed to go out on their own and take on responsibility.”

In the book, you explain how Germany’s difficult past informs this value on self-reliance.

“Yes. They had this horrible upheaval with the Nazi years and the generation that followed, the ones that grew up in the 1950s and [who would be equivalent to] our Baby Boomers, really rejected everything their parents were about, for obvious reasons. They were very anti-authoritarian, almost to the extreme. For example, they had childcare centers that had almost no rules at all. It’s been more moderated since then, but you will still find really strong resistance to any kind of harsh discipline of kids or any controlling way of viewing kids and handling kids. Not just physically, but in terms of ideas and information. German parents don’t withhold uncomfortable information from their children.”

You also question the notion of “attachment parenting,” which is fairly popular in the U.S.

“Attachment parenting as it’s been popularized by Dr. Sears, an American, is fairly extreme in terms. You have to hold your baby all the time, you have to be responsive two seconds after they cry, etc. Germans start teaching self-reliance starting at baby age. They’re more apt to leave their kids alone to play by themselves. They’re not in their face. They will put their babies down awake, which is actually common advice by a lot of sleep experts. Also, in terms of the theory itself, cultural anthropologists dispute the universality of attachment theory, that it’s more of a cultural [construct] instead of a truth. There have been studies of German infants that dispute the typical results of The Strange Situation Test by Mary Ainsworth [read more here]. Supposedly, [according to Ainsworth’s test] a really attached baby will cry when its mother leaves the room and be comforted when she returns. Well, in two different studies the German infants didn’t act that way. They acted like, ‘Mom’s gone, so what?’ They weren’t as ‘attached.’ And the argument there is, if two-thirds of German babies aren’t attached, that would mean there would be all sorts of mental problems in Germany, and that’s not the case. So, that begs the question—is this really what’s important here?”

What surprised you most about giving birth and raising an infant (your second child) there?

“The first thing, which I think is true of most of Europe, is that Germany actually has decent maternity leave. A lot of moms are home for the first year. They also have paternity leave and you’ll see more dads with babies. That was a huge difference for me. Also, there’s much wider acceptance, at least in Berlin, that childcare can be good for children. It was that attitude, more than anything, that surprised me. It was quite a relief, actually. In the U.S. we’re kind of taught that we use childcare because we have to. We have to return to work, but we wish that we could do the best thing for the kid, which is the mom being home with the kid all day until he is 5. That’s not the case in Berlin. The attitude is that children need other children and that new places and new experiences can be good for them. There’s a little bit less guilt there. Especially when I took my 1-year-old child to childcare. I saw how both of my young children loved going to Kita, which is a daycare/Kindergarten. They might have trouble leaving me in the morning, but by the afternoon when I picked them up, they never wanted to come home. Also, the whole outdoor thing is even big in the baby years. There are rain suits and teeny-tiny snowsuits. They are also less shy body-shame wise, and breastfeeding is big and done pretty much anywhere. And as they do in Germany and a lot of Nordic countries, parents will park a baby outside in a stroller and go into a restaurant.”

I’m assuming that the crime rate in Germany is also lower than the U.S.?

“There is actually the same amount of crime in Germany as there is in America. It’s a little higher, supposedly. The biggest difference is murder. The people I’ve talked to say that’s because the U.S. has more guns than Germany. But Berlin is not hugely more safe that a good neighborhood or a relatively safe neighborhood in the U.S.”

Tell us about what early education in Germany looks like. What stood out the most?

“There’s definitely an outside ethos. Our children had ‘garden time’ and took a lot of trips to nearby forests. We had a time called ‘toy-free time,’ which is usually a 3-month period where they take away all the finished toys and the children are left to create their own play from what they have around them and a lot of the time it’s about going outside. The kids are using sticks, they’re using chestnuts as money. The whole process really reinforces a lot of creativity, but it’s actually about dealing with future addiction. Kids are forced to deal with frustration and working together. It’s about developing their internal and social skills and concentration. That was very interesting. In the Kita program, they don’t have a lot of finished toys year round and they spend a lot of time outside, playing with what nature gives them. They make a huge deal about entering first grade. They have a big celebration at the beginning of school and the year is still a lot of play and not a lot of instruction. Traditionally, in Germany elementary schools are half day, and that is starting to change. It’s starting to get longer. At our school, it was half day and then there was afterschool care, called Hort. The kids would be taught until noon, have lunch, and they were playing until we picked them up. And even before Hort began, they would already have two recesses before noon. In Berlin, our public school was a Montessori school and I was impressed by the school choice. I was surprised they don’t allow homeschool in Germany. It’s against the law. They believe children have the right to society and their peers. So, you can get together with a bunch of other parents and start your own school, but you can’t keep them home. They had a lot of self-directed projects up until third grade, and not a lot of homework up until third grade, either. Once they got to third grade, they had a little bit of homework, but it was always done at school. Overall, it’s much gentler and more child-centered than what I see in the United States.”

What about the upper years—middle school and high school?

“Germany has that strict tracking system that starts early at fifth grade. That is changing, but it’s still a part of their society. There are three tracks—you’re definitely university-bound, you could go to university or a two-year program that they call ‘college,’ and the vocational track. That’s pretty old-school and rigid and I think there are some calls for changing that. I get the sense that there’s more academic pressure applied later. But they have no problem delaying it at the younger years.”

How is it that German parents can escape the fear and worry that grips many parents?

“As parents, we need to realize that there’s no way we can prevent all awful things from happening to our children. There’s no way to keep them perfectly safe. The effort to keep them perfectly safe hinders them growing up. Because we all have to learn how to manage risk in life. And I’m not sure why Americans feel we need to delay learning to handle risk so late. Some parents wait until their kids are 18 before they let them do anything. In Germany there’s a sense that you need to teach your child how to manage risk. It’s obvious in their playgrounds. They have regular playgrounds and adventure playgrounds, where children can build things, they can make fires, it’s acknowledged that it’s really risky to play there. They let the kids use their judgment on what’s safe and what’s not safe. You’ll also see children walk to school by themselves very early on. Our kids graduated into walking to school by second grade. By first grade the kids are still being walked to school by their parents almost the entire year. Towards the end of first grade my daughter had a lesson about traffic and her teacher took them outside and walked them around the neighborhood, showing them the crosswalk and how to navigate around the school. After that, we were expected to let our children walk on their own. I didn’t, because I’m American and terrified. I continued to walk her until she begged me in second grade. You’ll notice that around age 8 or so, children will be in the playgrounds in the cities without their parents.”

Why do you think Americans parent the way they do, even though they would also say they value freedom and independence?

“I think we’ve let the fear triumph. And that’s what you hear when you talk to parents all the time. They are so very afraid. I’ve read a lot of different theories on why this is, and one is that our media emphasizes and plays up anything bad that happens to a kid. Stranger kidnappings are really rare. There are only about 100 a year. It’s very low risk. But we probably hear of each one of those events in gory detail, which really heightens our fear. And we have shows like Law & Order, where every other episode is about a child getting hurt. But it doesn’t happen at that rate and it becomes exaggerated in our heads. So, there’s the physical fear, and then we have the fear that our kids are not going to succeed in life. That they have to have every minute scheduled to make the most of their childhood, so that they can get into a good college and get a good job. That’s a whole mindset that is really self-defeating for a kid. Because they look at that like, ‘I’m working really hard, so I can work really hard in college, so I can work really hard in life.’ Where is the fun in that and the ability to follow what they find interesting and their passion? There’s no opportunity in there for them to develop themselves. But not only can parents not control their child’s outcome, they don’t have the right to control that. Because that’s ultimately an authoritarian thing to do, to say, ‘This is who you are going to be. And this is what you’re going to do every day and every moment of every day.’ Parents have the best intentions. I don’t think parents are trying to be authoritarian. We’re trying to help our kids. But we have to step back to allow them to be themselves.”

What do you think American parents could best take away from these German practices?

“The biggest shift for parents is taking a hard look at your fears, and seeing which ones are realistic. Because if you can let go of some of those things, you will change the way you parent. On what you can do practically, you can teach your children how to walk and bike to places on their own. You can make it safer by putting a couple of kids together. What I’ve found is a lot of parents would like to do these things, but they have a fear of the culture around them condemning them. So, talk to your neighbors about it and other parents. I also make sure my kids have some time in their day, everyday, that they get to decide what to do for themselves. That means, I don’t overschedule them. I push back on excessive homework, which is actually very easy to do in elementary school. My kids play outside everyday. That’s another one that is really easy and I think it’s also a traditional American value, too. Another that is very important is to talk very openly and honestly with your children about difficult topics. Don’t keep them ignorant about important things like sex and death and not-so-rosy parts of our past. This is information they need to know in life. It’s a big part of life. If we keep it from them, we keep them vulnerable.”

For more on this topic, pick up the book Achtung Baby: An American Mom on the German Art of Raising Self-Reliant Children.

Share this story