How (Not To) Compare Your Children

Written by Lynn Berger

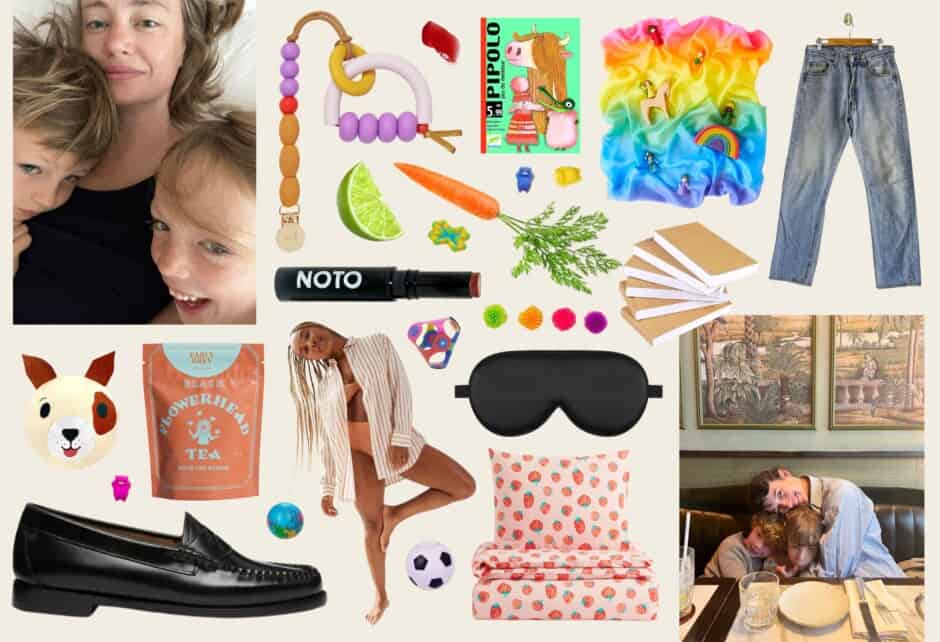

Photography by Surya Kishi Grover photographed by Maria Del Rio

If you’re raising more than one child, comparing your kids to each other is probably something you do—even if you don’t know you do it. But, as mother of two and journalist Lynn Berger explains, all of that comparison (either consciously or unconsciously, mentally or verbally) can have negative consequences. Below, the author of the brand-new book Second Thoughts: On Having and Being a Second Child—filled with thoughtful rumination and research about welcoming a second kid—shares her personal story, plus advice for breaking the bad habit of comparing children.

Until our second child was born, our first child was our only child. Other people’s babies aside, she came without material for comparison: she was terra incognita, and she taught us who she was, all by herself and on her own terms.

With our second child, things were different. He was different, of course—but he was also familiar, in the sense that we knew, more or less, what we were starting out on. He was like a wild, strange country we had visited two years before, and were now returning to: the terrain was still foreign, but this time we recognized the signpost.

And so, from the moment I was pregnant, I began comparing him to his big sister. I could feel his movements earlier and more often than I had my daughter’s; in utero, he had less hiccups and kicked with more force. My daughter had been born exactly on her due date: “he’s running late,” I grumbled, when I woke up on the morning of his due date with a belly still as round and big as it had been the night before.

The contractions came that night. At birth, he was heavier than his sister had been, and he cried longer, louder, and more heartrendingly than she had. In the first weeks and months, he fed more and more frequently. While our daughter had worn a somewhat fierce expression on her face in those early, feverish days and weeks, our son’s look, we thought, was one of worry and concern. A year in, he started walking a month later than she had. His anger tantrums didn’t last as long as hers. And where her first word had been “apple,” his first word was “that.”

It wasn’t that our son was doing better or worse than our daughter; it was that he was doing things differently—different in comparison to his big sister. In coming first, she had set a baseline against which we measured him.

Usually, those comparisons happened automatically, and only in our heads. Sometimes, my partner and I talked them over at night, noticing differences and similarities and wondering what they meant. What we didn’t discuss, however, was the fact that we were comparing at all: somehow, that process felt so natural we barely even registered it.

This changed for me when, on a stormy spring day when my daughter was around 4-years-old and my son was about to turn 2, I found myself in a conference room with ten other parents to take part in a parenting workshop on sibling rivalry. The cheerful, friendly instructor asked us parents to pair up and to describe our children to one another. I was teamed with a mother who, during the round of introductions, had told us about the constant fighting her two daughters engaged in, coming close to tears as she recounted it. At that point, my own children weren’t nearly as acrimonious toward each other; I had signed up for the workshop in part because I hoped to keep it that way.

When it was my turn to describe my children, I began with the eldest. I said she was sensitive, clever, curious, and somewhat afraid of failure. She’s sharp and funny, I said; and easily upset. The youngest, I continued, was more emotionally stable and perhaps also more cheerful. He seemed less clumsy physically and more adventurous; he was outgoing, good-humored and kind, but also quicker to anger.

When I finished speaking, I suddenly realized what I had just done: I had described my children in terms of each other; I had been comparing them. And while the comparison wasn’t to the advantage or disadvantage of either one of them, I still felt bad about it. For wouldn’t it be better, more fair, to go through life without a measuring rod in the shape of your sibling? To be seen as you are, not how you appear in contrast to someone else?

Parents who openly compare their children, the instructor told us after that initial exercise, may inadvertently create the conditions for sibling rivalry. After all, it may make them feel like you prefer one over the other, spurring them on to outdo the competition.

This was something I had worried about in the past, on days when sleep-deprivation and over-stimulation made me feel anxious and ill at ease. What if, I would think on those days, my tendency to mentally compare my children was somehow expressed in my behavior, in ways that I might barely notice myself? What if my son’s enthusiasm, for instance, cheered me up, in part because of its contrast to my daughter’s morning moodiness, or the other way around? And what if this meant that I somehow acted nicer, more warmly, to the one who made me feel the happiest at any given moment? Might all those subconscious signals shape my children, give them the feeling that I didn’t just love them for who they were? Might it make them see each other as rivals?

I remembered a paper I had read, about other ways in which parents’ comparisons might affect their children. A couple of years ago, a group of developmental psychologists studied 388 two-child families in the U.S. The children were teenagers, and the researchers asked the parents if their children did well in school, and also, who did better. They then compared the parents’ answers with the children’s school grades. As it turned out, most parents believed their eldest child to be the better student—even when that child didn’t actually achieve better grades. (Only if the eldest child was a boy and the youngest was a girl, did parents say that the youngest was more capable in school.)

What might explain these parents’ poor judgment? The researchers hypothesized that parents had a “higher” estimation of their firstborns because, compared to their second-borns, these children had long been operating at a higher level. They were already drawing princesses when the youngest child was still just scribbling all over the paper; already doing sums when the youngest was still learning to count; reading whole sentences when the youngest was yet to master all the letters in the alphabet. In other words: parents’ perception of their children was based not on those individual children, but on a comparison between them, and a difference in age registered as a difference in aptitude.

This came with measurable effects. For the researchers tracked the families for a couple of years, and what they found was this: if parents assumed that their children had different capabilities, those beliefs turned into expectations—and those expectations, as expectations often do, ended up shaping their children. “When parents believed one child was more capable than the other, that child’s school grades improved more over time than their sibling’s,” the researchers wrote. In other words: the comparison had become the basis for a self-fulfilling prophecy.

It seemed clear to me, as I sat in that conference room, that comparing is not without its discontents. At the same time, it seemed impossible to me for parents not to compare their children, at least from time to time. After all, we often see them together, and even when we see one child alone, it’s hard to forget everything we know about the other.

(Our children, too, are likely to engage in constant acts of comparison: psychologists have known for a long time that people have an innate tendency to compare themselves to others in their group, and to partly base their sense of self-worth and identity on the result of that comparison. And if there’s one person who is nearly almost around and available to figure in that process, it’s your sibling.)

Comparing, then, is what we do. Does this mean we’re doomed to set our children up for competition, and to shape their development because we come away from our comparisons with different expectations for each of them?

Not necessarily. Once I became aware, after that exercise, of my comparison-driven mind, I couldn’t become unaware of it again. And so it was there that something started to change. As is so often the case, simply being mindful of whatever tendencies you might have can help you, if not to root them out, then to mitigate them at least.

These days, whenever I find myself thinking that my son differs from my daughter in this or that respect, or the other way around, I catch myself. I remind myself to try and look at this one child in isolation as much as I can. I never succeed completely, of course—what is parenthood, anyway, if not a prolonged exercise in not living up to the ideal parent you have in mind? But such reminders do help me, in those moments, to focus my attention—and to try and become a better observer of my individual children.

At the end of that workshop, our instructor reminded us that, even if we cannot eradicate our inclinations to compare, we can try, as much as possible, to not behave accordingly. She showed us how, in the form of simple, concrete examples. “Don’t tell the youngest child to eat nicely like his older sister, just say you see he’s playing with his food,” she told us. “Don’t say your eldest gets upset much faster than her little brother, just say you see a girl crying, and ask her to help you understand her tears. Don’t project, don’t compare, just look and describe what you see, one child at the time.”

I’m still hoping that one day, I’ll be asked to describe my children again. Next time, I’ll do it differently: I won’t describe them in terms of each other. Because if the way we see our children influences the way we treat them, then perhaps the opposite is also true: that a different view of our children can begin simply with a different way of speaking—both with them and about them.

Lynn Berger’s new book, Second Thoughts: On Having and Being a Second Child, is firstmost a personal reflection of her own pregnancy with her second child—her worries about sibling rivalry, splitting her already limited time in a day between two children, and struggling to look at each child’s development separately without reflexively comparing the two. Second Thoughts also explores the careful research Lynn undertook to investigate the common tropes she saw dominating most sibling literature in order to discover which, if any, hold any truth. You can purchase Second Thoughts on Amazon and Bookshop.

Share this story