Are You Doing Time-Out All Wrong? Here’s How To Do It Right

Written by Katie Hintz-Zambrano

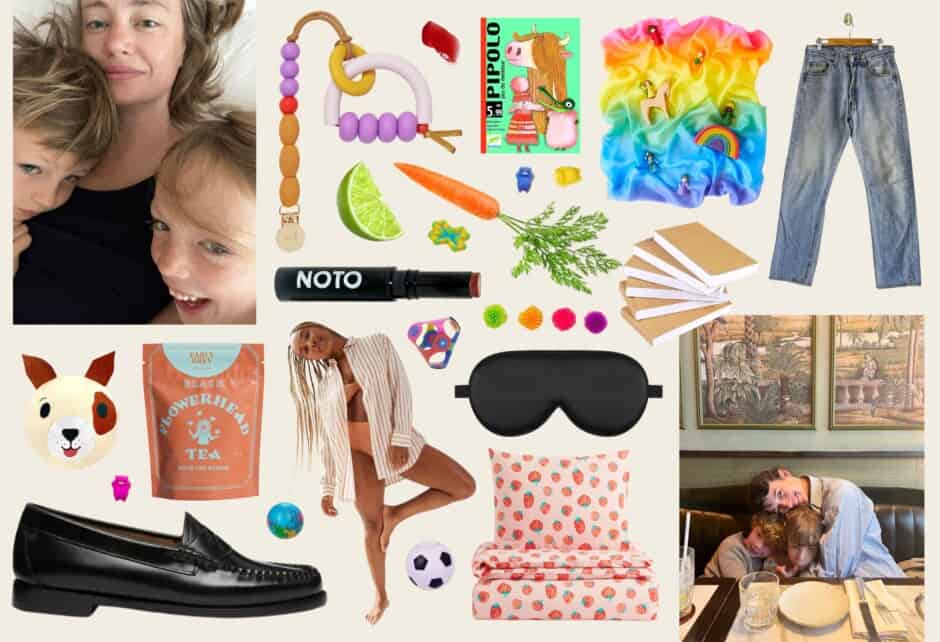

Photography by Mary Elizabeth Ford's home, Photographed by BELATHÉE PHOTOGRAPHY

If you’re the mother of a youngster, time-outs are often a way of life. But, could you be doing them more effectively? After seeing hundreds of parents fumble in their attempts at enforcing successful time-outs, Andrew Riley, Ph.D., who specializes in behavioral pediatrics at Oregon Health and Science University, did a 1-year study of 401 Portland-area parents to come up with a handful of methods that’ll strengthen the discipline practice (and hopefully eliminate the need for so many time-outs, long term).

“I was repeatedly having the experience of talking with parents about time-outs. Many times parents would say they’ve been trying time-out, but it doesn’t work,” says Riley. “Usually I can ask a few questions and find out why the time-out isn’t working and we can adjust that in some ways to make it a lot more effective. We did this research with pediatricians in mind, identifying the common areas where we can make time-outs more effective, so pediatricians can counsel parents more effectively.”

Of course, not only pediatricians can benefit from this knowledge. We went straight to the source and asked Riley to clear up the misinformation around time-outs and spill his tips for how to strengthen the practice at home.

Revisit The Purpose Of Time-Out: “We saw that parents don’t necessarily have a clear idea about what the purpose of time-out is. The purpose is to decrease the future occurrence of the behavior. That’s the flat definition. Often more of these pop-psychology ideas showcase time-out as a way to give your child time to think about what they did. Whether that’s true or not, that’s not the crux of what time-outs are about and how they work. That misunderstanding can lead to some of the mistakes in implementation that we see.”

Give Only One Warning: “Only ever give one warning before a time-out. You really don’t have to give any warning, but sometimes warnings can be useful, because they can often save you from having to give a time-out. But limit yourself to just one warning. Then, once the time-out starts, you want to eliminate as much talking and interaction with the child as you can.”

Cut The Chatter: “One of the biggest mistakes we’ve seen is parents talking to a child during time-out or too much talking on the front end of the time-out. A lot of times where that comes from is that parents want to explain and make sure that it all makes sense to the child. But really that’s not how it works. The way it works is going from time-in, which is the more interesting and stimulating environment, to time-out, where the emphasis should be on making it boring. You want to make the time-out environment as boring and unstimulating as possible. Talking from the parents is actually something that’s really stimulating and interesting to kids. So, even if it’s in the format of a lecture or ‘talking to,’ that’s still contaminating the time-out and making it so it’s not as effective.”

Get Rid Of Stimuli: “In addition to not talking to your child, you also want to limit their access to any other stimulation. So, the T.V. should go off and we generally don’t want to send kids to their bedrooms, since they usually have really interesting stuff in there most of the time, and things to play with.”

Focus On Quality Time-In: “Time-out is only as good as time-in. With time-in being all the attention, love, and warmth, access to privileges, and all of the fun and interesting things children can receive. Time-out is just about the removal of those things. If you don’t have quality time-in, then time-out is not going to work. Time-out is not meant to be a bad thing, it’s just meant to be a pause on the good things. And so sometimes when time-out isn’t working, it’s not that we need to focus more on the time-out, it’s actually about focusing more on the positive and enriching that end of things before the time-out is going to be effective.”

How To Keep Kids In Time-Out: “One of the biggest reasons parents say time-outs don’t work is because they say their children don’t stay in time-out. And there are some things to do to prevent that. One way is to make sure your child is calm and cooperative before they end their time-out. We want to show them that being calm and cooperative is the way that the time-out is going to end. Typically, if you can do that in a kind of preemptive way, it curtails those problems with kids and they learn to serve their time, so to speak. Another way to keep kids in time-out, especially with young children, is repeatedly taking them back to the time-out spot, and with minimal interaction and talking. Sometimes that takes persistence, which can be frustrating for some parents. Another way to keep kids in time-out is to use a ‘walking time-out’ or a ‘deferred time-out.’ This means if kids get up out of the time-out area, you don’t really do anything to try to put them back, but you continue to ignore them and you don’t grant any requests until they go back and serve their time. There’s no magic to sitting in a chair in a corner for time-out, it’s really about the broader concept of, nope, we’re going to keep things really boring and unstimulating until your behavior is more appropriate.”

Time-Out In Public: “Time-outs in public can definitely work, but can be tricky to execute and it’s probably best to make sure time-outs are going well at home before trying it in stores or other public places. As long as you can make things boring, you can do a time-out. One little trick that some parents find useful is to have a small hand towel or handkerchief stowed away in a pocket or purse. Then, if a time-out needs to happen, the towel goes on the floor and that becomes the time-out spot. Time-out or any other behavioral teaching strategy is going to be most effective when it is applied immediately after the behavior its meant to alter, so the ‘you have a time-out when we get home’ approach is weaker, but some psychologists suggest doing that if there are not better options. I think that’s most likely to work with school-aged children who already have experience with time-out and what it means. My general advice about managing behavior in public is to 1. make sure you’re giving kids clear expectations for what you want (‘Stay right next to me please’). Having them help by pushing the cart or grabbing items off the shelves is another way to direct behavior appropriately. 2. Provide lots of praise and attention for appropriate behavior (“Thank you for staying close just like I asked! I really like that!”). Focusing on the positive first is always a good idea.”

Ideal Ages For Time-Out: “Time-out can start as young as 12-18 months, although at that age most kids aren’t doing behaviors that necessitate a time-out. We usually like to save time-out for things like aggression, destroying objects, or things like that. Usually those types of behaviors aren’t happening at really young ages, but sometimes children will do something that’s dangerous or inappropriate and time-out will work. If your 18-month-old bites you, maybe you turn him away from you on the floor for 30 seconds. The idea that children need to be old enough to ‘understand the concept of a time-out’ is a common way parents look at time-out, but it’s actually not an accurate way in the case for how the behavioral learning works. This type of learning is really happening as soon as they are born. Their behavior is being shaped by the way they interact with their parents and the world around them, and time-out is just an extension of that. The most fundamental way we learn is through the consequences of our behavior. So, if we do something and something good happens, you’re going to keep doing that. If you do something and nothing good happens, you’re probably not going to do it again. And you don’t have to understand that in a cognitive way. If you can do a really good job with time-out in the toddler stage, then you’re probably not going to need it much later on. Although there’s research with time-outs and children up until the age of 10.”

All Kids Are Different: “We’re not saying time-out is the end-all, be-all. It can be really useful for some parents, but not every parent needs it. Different kids respond differently. Some parents could make every one of the mistakes I mentioned above. They could do it in every way I don’t recommend, but their kid could respond fine, because he’s an easy going, good-natured child with behavior that’s easier to manage. But for kids that are a little more challenging and strong-willed, that’s when these details become more important. At the same time, those are the same parents who often feel that time-outs aren’t working, but in reality those are the families that just need to create a stronger version of a time-out to make it work.”

Share this story