The Author Of “The Great Mother” On Motherhood In 20th Century Art

Written by Katie Hintz-Zambrano

Photography by Photos Courtesy Of Skira

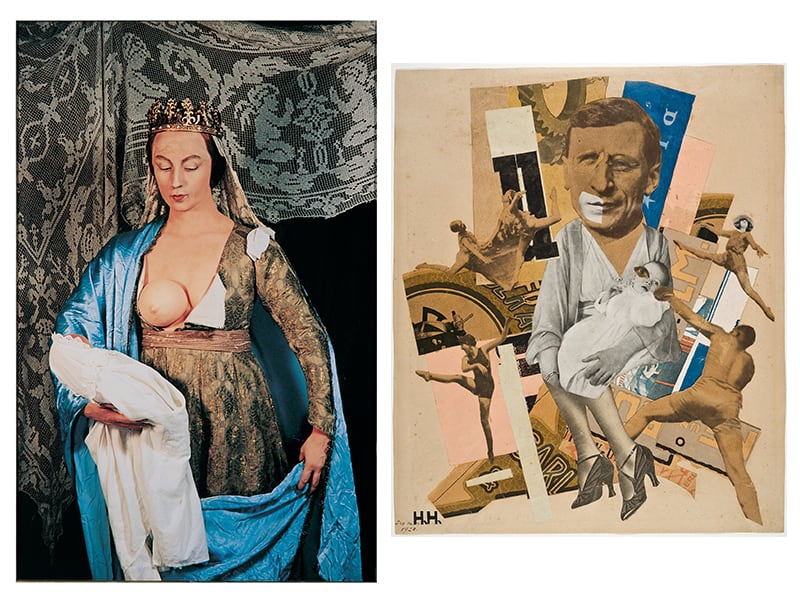

When we heard about the Milan-based exhibit, The Great Mother, last August, we were understandably obsessed. Spread over 20,000 square feet at the Palazzo Reale, the exhibit featured 127 international artists, with works created throughout the 20th century up to 2015, all depicting the idea of maternity through art. It’s all the brainchild of Massimiliano Gioni, the artistic director of both the New Museum and the Nicola Trussardi Foundation, and a brand-new father himself. Luckily, for those who missed the show, Rizzoli has just released The Great Mother book, which takes a deep dive into the exhibit and the politics of motherhood and art, with pieces by both unknown artists and big names like Cindy Sherman, Catherine Opie, and Rineke Dijkstra. Below, we got the low-down on the exhibit and new tome from the man behind it all.

What inspired you to create the Milan exhibit?

“I think there were three factors. First of all, I had been thinking about an exhibition that could address the gender disparities that are still at play in the history of art, but wanted to find a different perspective to address these questions. I didn’t want to simply complain about gender disparities, but to find a more affirmative point of view, so to speak, and I realized that maternity and motherhood could be an interesting theme through which to observe the changes in gender and sexual roles across the 20th century. Secondly, the more I started thinking of this theme, the more I realized that it immediately touched upon so many crucial questions and topics throughout the 20th century, and well beyond contemporary art: the relationship between individual and state for example, the relationship between psychoanalysis and art, the struggle for emancipation and recognition of the feminist movement and its impact on art, and many other experiences that defined the last century. More broadly, the exhibition became a reflection on the relationship between power and women in the 20th century. Finally, there was also a biographical component, or maybe a talismanic component, to the exhibition and the book. My wife and I had a baby who was born 3 days before the opening of the exhibition, so we were experiencing some of the very same changes that many works in the exhibition described.”

Tell us about the book as an extension of the exhibit.

“The book pretty much translates the experience of the exhibition in print form. It was created as a catalogue of the exhibition and the whole idea was that it could live on by itself, independently from the exhibition, and I think the essays by many great art historians and writers, such as Whitney Chadwick, Lucia Re, and Ruth Hemus, really have contributed to give the book a much longer shelf life. The book does not present a pretty picture of motherhood. Many works are tough and critical and visceral. As Simone De Beauvoir said, across the 20th century all the eccentrics attack the representation of motherhood. They probably do so because motherhood was perceived as a stand in for all the most conservative and oppressive values of tradition. As a result, motherhood as seen in the work of many artists is a battleground and not necessarily a pretty picture of love and affection.”

How long did the research process take?

“It was an exhibition I had been thinking about for a while and there was also an interesting predecessor: an unrealized exhibition about motherhood by legendary exhibition organizer Harald Szeemann. So, I had been thinking and researching some of these themes for a few years. When we started working on the actual exhibition and the book, we worked on it for one and a half years and it was very much a team effort. We had a team of writers and researchers working on various themes and subthemes of the exhibition. I think some of the most important steps in the research were reading or re-reading some of the canonical texts of the feminist movement, such as Simone De Beauvoir’s The Second Sex and the writings of Carla Lonzi, an important art critic and historian who eventually quit the art world to devote herself solely to the militancy of the feminist movement. Also, the the extraordinary Of Woman Born by Adrienne Rich and many other wonderful texts, many of which, as banal as it sounds, literally changed my life and the way I think of myself and the ones around me.”

What were some of the most surprising things you learned or uncovered while researching this book?

“I think the chapters dedicated to futurism, dadaism, and surrealism are particularly interesting and rich and they offer a much more complex understanding of art at the beginning of the 20th century. Many of these avant-garde movements did a lot to transform the perceptions and narratives around sex and gender, but in most cases they were also intimately rooted in 19th century views of family values, so they were at the same time incredibly revolutionary and conservative. When it came to the role of women in these movements, they were both idealized and marginalized, but I think their contributions took the premises of the avant-garde a step further than their male colleagues. If the avant-garde is based on the dissolution of any distinction between art and life, many women artists of the avant-garde went much further in living their life as a total work of art. Sadly, what the book also shows is that many of the slogans and proclaims of the avant-garde, which often used love and sex as tools for a social revolution, were much easier to formulate for men than for women. One thing was to believe in free love, when you were married and were having affairs and getting your lover pregnant, and another was being the lover in that affair.”

What are some of your favorite art works in the book?

“Well, to use an appropriate metaphor, choosing one work over another would be like preferring one child over another. It is simply impossible. I can say that we were lucky to have amazing paintings by Frida Kahlo, Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning, Leonor Fini, and drawings, photos, and collages by Lee Miller, Dora Maar, Unica Zurn, Valentine Penrose, Toyen, and many others, all in one room dedicated to surrealism, and it doesn’t happen often to be surrounded by so many masterpieces. In one room we presented 48 original collages from Max Ernst’s ‘The Woman with 100 Heads,’ that alone was quite incredible.”

What sort of dialogue do you hope the book will bring?

“I was born in a province outside Milan and one should never underestimate the power that a book can have on the life of a kid somewhere in the middle of nowhere. If I were to be extremely ambitious, I would love that this book could end up in the hands of a 14-year-old who maybe is trying to figure out exactly how to accept himself and his weirdness, which is another way to say his or her humanity, and discover that there are so many other freaks out there.”

Do you hope to have the exhibit you created travel?

“I am a bit of a traditionalist when it comes to exhibitions. I actually think that the viewers have to travel, not the exhibitions. The show in Milan was set in a series of magnificent rooms in the former royal palace in the city of Milan, a masterpiece of neo-classical architecture that preserves original tapestries and furniture. So, it was not a neutral museum, but a space charged with strong atmospheres. And we installed the exhibition as a kind of ‘doll house,’ to quote the famous Henrik Ibsen’s play, which played a crucial role in redefining the image of women at the end of the 19th century. More specifically, one thing is to speak about motherhood and birth control or gender inequality in Milan and another in Manhattan. I thought that in Italy some of the polemical arguments of the exhibition resonated more strongly.”

Who are some mothers—your own, throughout history, friends, or famous people—that inspire or intrigue you?

“Last year Maggie Nelson published a short autobiographical text about maternity and gender, titled The Argonauts, and she speaks of the ‘many gendered mothers of my heart’ to describe the many figures who take on the role of mothers, independently of their biological background. I think this exhibition presented the work of many great mothers of the avant-garde, such as Mina Loy, Baroness Elsa Von Loringhoven, Emmy Hennings, who are still unjustly lesser recognized than their male counterparts.”

You became a first-time father in August. Would you ever do a book or exhibit exploring fatherhood?

“Unfortunately, fatherhood has pretty much monopolized any discussion of art and power throughout the 20th century already. Actually one of the saddest realization as I was working on this show was to see how much any discussion of motherhood in the 20th century actually always turned into a discussion about fathers and about the state. So, no, I don’t think I will be doing a book about fatherhood. Or better, if I were to be too ambitious, one could say The Great Mother is my version of an anti-patriarchal history of art in the 20th century. And I say this with the greatest modesty and fear—I am sure many will criticize it for being still a bit too masculine.”

The Great Mother: Women, Maternity, and Power in Art and Visual Culture, 1900-2015, $29.47, Amazon.

Share this story