Mom Talk: How to Celebrate a Bad Mom on Mother’s Day

Written by

Photography by

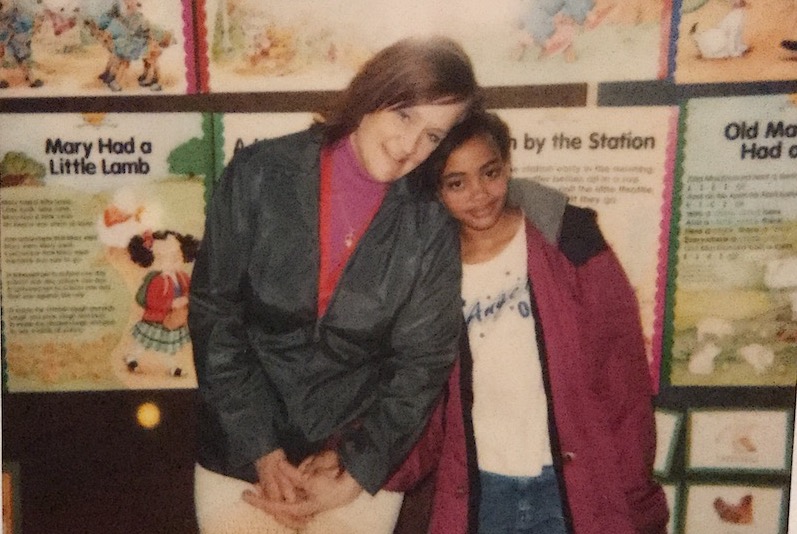

Photo courtesy of Shaquille Heath

For many people, Mother’s Day can bring about some complex emotions, whether it’s grief from not having a mom around to celebrate, or resentment from having a mom not particularly deserving of a celebration. On today’s Mom Talk, Shaquille Heath talks about the crossroads she finds herself at each year around this time, since, as she writes, her mother “was not a good one. In fact…she was a really, really bad one.”

I’m not a mother myself, but I’ve known enough mothers to understand that motherhood is messy. I’ve read enough articles to understand that dropping your baby once or twice is as much of a rite of passage as loosing your first tooth. I’ve watched enough movies to expect the moment when a mother locks herself in a closet or bathroom to take a few minutes to breath by herself. I have enough nieces and nephews to know that one of my sisters is missing a nipple from breastfeeding, and the other is only just getting rid of the bags under her eyes because her two year old hasn’t slept through the night since the day she was born.

Most importantly, I know motherhood is messy because I’m a human person who has had a mother. And that mother was not a good one. In fact, I dare say, she was a really, really bad one.

So, as Mother’s Day starts to creep onto the calendar, as it does every year, I find myself at a crossroads. I’m not interested in watching a commercial where an apron-wearing beauty sends her kids off to school, and watch as that lucky child pulls out a peanut butter and jelly sandwich that was perfectly cut into a heart. I’m not keen to walk down the holiday aisle at Walgreens and observe as people debate between a card that says “Best Mom Ever” and “Love is Where Mom Is.” I struggle with processing this holiday because even when the cards or the commercials or the articles talk about the messy things, they don’t talk about the bad things. And I’m left wondering, how do you celebrate a bad mother on Mother’s Day?

My mother was a force. 5’10” with long lean legs and curly red hair, she was the kind of woman that people craved to be around. Her aura radiated warmth, making complete strangers feel that they could share their entire truths with her. But what really fills my memories are the ones of her singing.

Being in the presence of my mother meant you had the pleasure of enjoying a live performance every day. Her eyes closed, she’d move her hips side to side, and sing like no one was watching. And at most times they weren’t…but I always was. There was never a more beautiful woman in the world than my mother when she’d throw her head back to hit the high notes of Celine Dion’s “To Love You More,” highlighting her long neck and bold cheekbones, which, with the help of genetics, she would pass on to me.

Although we didn’t have much in our house, or in general, we always had music. An eight-track player sat beneath a tape player, which rested upon a CD player, topped with a record player. I can think of memories where I was so small, the speakers on each side of the stereo stood taller than me. Together, my mother and I would put on grand performances for an audience of no one. I’d stand on the couch and eye-to-eye, we’d sing so close that I could always feel the warmth of her breath on my cheeks.

But this beautiful, captivating, singing woman had an intense drug addiction. It remained in the shadows while I was young, but I’d come to know it well as I got older. Her addiction was like a wall covered in ivy. The growth so slow, you wouldn’t see it at first, but then one day, you’d walk past the wall and realize it was all green. You’d wonder how you had walked past that wall every day and never noticed the change, the creeping of the ivy, the swallowing of the cement. But again, you’d continue living, the green ivy becoming your new normal. And one day, it would become so familiar, you’d forget what the bare wall had looked like, and wonder if there had ever even been a wall there at all.

While my mother fought her drug addiction, I became addicted to our sing-alongs. When she wasn’t home, I would position myself just like her in front of the stereo. Opening a CD case, I’d pull out the lyrics book. Song by song, line by line, my goal was to memorize all of the words, so that the next time we had a sing-along, I would know even more lyrics than the last time.

But eventually, as it typically does, the addiction swallowed her. My beautiful, forceful mother became a woman I didn’t recognize. One who would keep me up until 3 a.m. on school nights to clean the entire house with bleach. One who would dissapear for days at a time, leaving me to fend for myself on getting to school or food to eat. One who made me sit outside in the middle of winter as punishment for confronting her about the drugs I found.

For so many years the two of us lived in our own little world. At that point, not only had I become my mother’s best friend, I had become her only friend. But I knew this wasn’t life. I knew that I didn’t want this to be my normal. If I stayed, it would only be a matter of time before the ivy would swallow me, too. So, I had to go.

I thought I could be mad at her forever. That I wouldn’t talk to her ever again. Not until she was clean. Not until she was better. But then I turned 15, and she got sick.

It took a year for my mom to succumb to her brain tumor. The last nine months, she wasn’t herself at all. I consistently had to remind her who I was, and by the end, she wasn’t even able to talk, let alone sing.

The last time I saw her, she was laying in a hospice bed. I was 17. Her body lay lifeless on a small mattress, propped up off of the clinic’s floor. Instead of music, the only sound that filled the room was the beeping of her heart monitor. I didn’t want my last memory of her to be of that room, so I faced the opposite direction. I let her know that I missed her. That I had also missed our sing-alongs all of these years. And that I couldn’t wait for us to be able to sing together again.

Three days later, our roles would reverse and she’d leave me…only this time it would be for good.

As Mother’s Day starts to rear her head again, I feel the ambivalence. The anger. The nostalgia. The regret. I struggle between honoring her memory with a Facebook post or drowning myself in a bottle of wine. I wonder if I can finally forgive her for her addiction, understand her missteps and shortcomings were because of a disease. Or if the anger that I feel is what actually better serves me. And eight years later, I still don’t have the answer.

Regardless, a picture of her sits on my bedside table. In it she looks back over her left shoulder, smiling brightly at the camera. She looks healthy. She looks happy. She looks like my mother.

Shaquille Heath is a communications professional and writer whose work has also appeared in The New York Times. This essay was originally published on May 3, 2019.

Are you a mother with something to say? Send us an email to be considered for our “Mom Talk” column.

Write a Comment

Share this story

Powerful and beautiful honesty. A gifted writer and woman