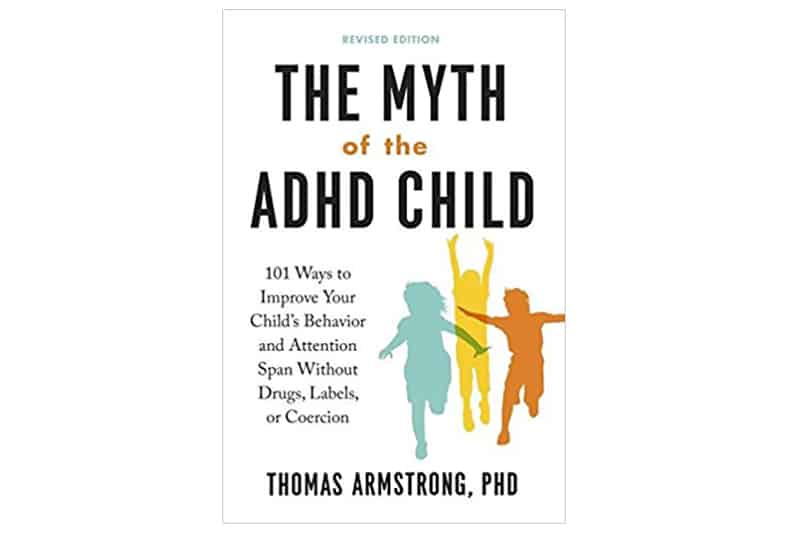

The FDA recently approved an amphetamine-like candy for children. It’s a disturbing development, but just one of many in the investment Big Pharma has in the recent spike of diagnoses of children with ADHD. To Dr. Thomas Armstrong, author of the newly revised The Myth of the ADHD Child, it came as no surprise. Armstrong believes Big Pharma has been manipulating the conversation around ADHD for the past two decades and he has re-released his 1995 anti-psychostimulant plea with statistics reflecting the admittedly alarming trend of the medication of children with ADHD.

Armstrong details the history and politics of the rise of ADHD diagnoses in the first half of his book. The statistics and the admittedly damning details of various pharmaceutical company relationships with the ADHD community are frightening. The second half of the book is a guide—a how-to of sorts—for parents of children diagnosed with ADHD. He stresses that the book is only to be used in conjunction with your child’s doctor. But, he equally stresses the need for parents to take a personal and proactive role towards such a diagnosis and to employ his 101 strategies (or a combination thereof) alongside medication.

The title may lead some to concur that Armstong believes neither in the diagnosis of ADHD nor the medication used to treat it, and he may well not. But, what Armstrong concludes is a gentler compromise; one that embraces the child’s behavior, attempts to nurture it, and gently leads toward a balance between the needs of the parent (or often the teacher) and the spirit of the child. He does not advocate that any parent remove their child from medication. Though you get the sense he wants to, he is not that irresponsible. He does advocate for a more thoughtful approach to medicine and for informed parents to not blindly trust in the purported safety and preeminence of the Church of Big Pharma.

Armstrong builds his case for lighter pharmaceutical-intervention with ADHD on the research that found that ADHD children are, developmentally, just two to three years behind their contemporaries. They are, in this sense, developmentally delayed. And, in the very nature of a delay, eventually they will catch up. In fact, only .8% of children diagnosed with ADHD will still show for the disorder by the time they are 20. And yet, despite the fact that it is—mostly—a temporary affliction, these children are prescribed (and in Armstrong’s view thoughtlessly so) psychostimulants of the variety that are classified by the FDA as Schedule 2 drugs. On the FDA’s website, Schedule 2 drugs like Adderall keep the unpleasant company of such notorious friends as Vicodin and Oxycontin. These drugs are, as defined by the FDA, known to have a “high potential for abuse, with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence.”

Armstrong argues that it is nurture not nature that accounts for the sudden rise in ADHD diagnoses (every year since 1997, the number of kids diagnosed with ADHD has risen by 3%). He rails against the rigidity of public schools that require young children to sit still most of the day. He argues, predictably, against the pervasive use of media in our children’s lives and education. He resents the resulting lack of outdoor, free, imaginative play.

The first half of Armstrong’s book can feel like a lecture—what parents, doctors, teachers, and researchers are all doing wrong. But, the latter half is more uplifting. Filled with 101 “strategies”, this half aims to help parents who are stressed at the diagnosis of a child to find other ways to help that child (in addition to medication, albeit at a hoped for lower dose). He asks dozens of hypothetical questions to the parent and refers them to his various strategies of which he describes in thoughtful detail. For example:

Does your child tend to have a mind that wanders, attention that drifts, and/or a penchant for daydreaming? See Strategy #7: Teach Your Child Focusing Techniques, Strategy #43: Teach Your Child Mindfulness Meditation, and Strategy #54: Consider Neurofeedback Training.

Or,

Does your child have a good imagination? See Strategy #2: Channel Creative Energies into the Arts, Strategy #20: Nurture Your Child’s Creativity, and Strategy #84: Let your Child Play Video Games that Engage and Teach.

Armstrong believes wholly that ADHD children are not broken, not wrong in any way. He believes they are developmentally different and that such a difference can be a beautiful, creative, wondrous thing. He understands the frustrations of parents and teachers, but he advocates for working with the child’s mind and not for drugging it down.

Parts of Armstrong’s The Myth of the ADHD Child run on in a semi-coherent lecture leaving you wondering at the length and strength of your own attention span. But, as a whole, the book comes away with an optimistic view of ADHD and of the children we diagnose as such. Any parent with concerns for their own child’s diagnosis could do well to read Armstrong; not as a replacement for a medical professional’s prescriptions, but as pocket-sized wellspring of alternatives and additions to your child’s care.

For even more book reviews, be sure to check out our thoughts on Gentle Discipline, How Do I Explain This To My Kids?, and The Vanishing American Adult.

Share this story